Music Royalties Explained: The Ultimate Guide for 2025

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links, and we earn a small commission from purchases at no cost to you. We only refer products or services we know and trust.

Introduction

One of the biggest mysteries and struggles of the music industry is how to get paid music royalties in the United States and beyond. We all too often hear about the cliché starving artist criticism (especially from mom), but what about the artist that eats? How do musicians at the top of their game reap what they have sown? You are in the right place, my friend. Let's learn about the different types of royalty that are available to you, collection societies, and how you can collect royalty payments for your original songs.

Start with this video:

Why I made this guide

Since starting the Indie Music Academy, I’ve helped independent artists like you get over 100,000,000 streams on Spotify using marketing strategies that work. As you can imagine, this generates a TON of music royalties, but I quickly found that most independent artists are not properly registered and are leaving a lot of money on the table.

I created this guide so that you can be knowledgeable of not only the different types of royalties and how to collect them, but also understand what percentages are fair so that you get paid what you are worth when negotiating your contracts.

Yes, I realize this blog is extremely long. That's why I made all of this information available for download so you can access all of this offline! Click the button below to save this article to your email (completely free).

Short on time?

Get the Free Music Royalty Collection PDF

What This Guide Will Not Do

I want to take a moment to be clear. Following the steps will not increase the amount of usage your music will receive. You only earn royalties from your fans actually enjoying your music. If you need to Grow Your Fanbase to Increase Your Income, place that higher on your to-do list and place these registration steps second. These steps, once implemented, just open the pathways for money to stream into your bank account—but you still need to turn on the cash flow with your music first. The key to a music income is growing your fanbase slowly and steadily, and with the steps below, you will grow your income as you grow your fanbase. Are you ready?

Here is What You’ll Learn:

Check out the table of contents below for the types of royalties involved. Each topic is linked to the information within the guide. Read all the way through for a comprehensive understanding, or jump from link to link for quick reference.

Table of Contents

The Different Types of Music Copyright

No Tommy Wiseau, we are not kidding. There are actually two types of music copyright and both are important if you want complete control of your music and your music royalties. The two types of copyright for every song consist of the Sound Recording Copyright and the Songwriting Copyright for the actual musical composition itself.

1. Sound Recording Copyright

This is a little hard to understand at first but it will makes sense. The copyright of the recorded song (AKA the "master recording" or "masters") belongs to the owner of the master sound recording. So just remember this: Master=Recording. Master rights usually belong to either the artist(s), record label, recording studio (if the artist is unable to pay for recording services), or any other party that financed the recording. The reason that Master Rights exist as its own copyright is that if you record your own version of Michael Jackson's Thriller, recorded in the style of Ska-Punk, you are creating a different audio recording with different musicians, at a different studio, recorded at a different time, with different money, etc. Therefore the master itself is a different piece of intellectual property, even though the melody and the lyrics of the song itself remain the same. It's the lyrics and the melody that takes us to the next type of copyright: songwriting copyright.

But before moving on remember: if you are the rights holder for the sound recording of your music, you may want to register that work with the US Copyright Office.

2. Songwriting Copyright

So let's continue pretending that you are recording your version of Michael Jackson's Thriller. In order to have permission to use the music and lyrics in the first place, you need to obtain permission to use the song itself, also known as the composition copyright. Even if your intent is to recreate the recording just as I described above, there is still intellectual property contained within the lyrics and the melody of the song that is separate from the intellectual property contained in the sound recording. That “permission” you need to make a new recording of a song is called a “license.” Thankfully, there is something called a “compulsory license” that grants you permission under US Law for some usages. For example, a cover song DOES fall under this compulsory license, so all you need to do is pay the license fee and you’re automatically accepted. More on this in our How to Cover a Song the Right Way article.

Note that if your cover song is a faithful reproduction of the original music composition (same melody, lyrics and structure) and you are only releasing it on streaming platforms (not available for download or purchase anywhere, i.e. iTunes and Amazon) then the streaming services will handle any publishing royalty payments to the respective parties, so long as you list them in the metadata of your release. This is the most straightforward way to release a cover song (if slightly boring because it doesn’t leave you much room to play around with your own arrangement).

For other usages, such as in a film or commercial, you need to get real permission. In order to get permission to use a copyrighted musical composition, you need to contact the copyright holder and obtain publishing rights. Publishing rights belong to the owner of the actual musical composition. The publishing side of music refers to the notes, melodies, chords, rhythms, lyrics, and any other piece of original music. If you wanted to use a composition AND a recording that you didn’t write or create, you’d need TWO licenses. One for the song, and one for the recording. This is the classic example of both types of copyright being required for the usage of a popular song (and the recording that popularized it). So when copywriting a piece of your own music, or requesting permission to use a piece of music owned by someone else, you need to keep in mind both types of copyright, Sound Recording, and Songwriting.

If you are the Publishing Rightsholder, meaning you are the owner of the songwriting copyright, or you have obtained control over the piece of music, you may want to register that work with your Performing Rights Organization.

3. Who typically owns a music copyright

The songwriter is always the initial owner of the song’s copyright, but copyright can be transferred to other parties when the artist is signed to a record or publishing deal. As you read above, things can get complicated when there are multiple parties involved, so let’s break down the most common Music Copyright Examples.

Independent Recording Artist

An independent recording artist who writes their own music and funds their own recordings (whether through paying for studio time or recording DIY at home) will own both Songwriting and Master Recording copyrights.

Artist Signed to a Record Deal

A signed artist usually forfeits their Master Recording copyrights to the record label when signing their record deal. In exchange, the record label will fund the studio time and production cost up-front for the artist. This might sound like a sweet gig, but don’t forget that many record deals are 360 Deals where a percentage of the artist’s non-music earnings will also be taken by the record label to recoup the recording costs. In addition, many record deals also include a baked-in publishing deal so the next section will also apply.

Artist Signed to a Publishing Deal

An artist signed to a publishing deal forfeits their songwriting copyright ownership to the publishing company. For signed artists, this means that the Label/Publisher will own and control the musical composition in addition to the master recording when they acquire publishing rights. Non-performing songwriters are often signed to a Publishing Deal in order to write songs for other artists. These professional songwriters get paid a salary (aka a “Writer’s Draw”) from the publishing company to cover bills, rent, etc. One important thing to note is that while songwriters lose their publishing control and royalties to the publisher, they still retain credit as a songwriter and will still receive the songwriting portion of their performance royalties from their Performing Rights Organization.

To learn more about becoming a professional songwriter, check out our post about Songwriting in Nashville.

4. How to Copyright Music

Before you go spending a bunch of money at the US Copyright Office, let’s make sure that your song is even eligible for copyright. This is straight from the US Copyright Law:

“You can copyright music, copyright lyrics, or copyright both. You may copyright a new song or a new version or arrangement of an existing song. The song must be your original work, meaning that it must have been created by you and must show some minimal amount of creativity.

You can’t copyright a song title or a chord progression. If you make an audio recording of your song, you may copyright the sound recording in addition to your copyright in the song itself.”

So just to be clear, you can’t copyright your song ideas, only songs themselves. To become the copyright owner of a song you need to register an account at the US Copyright Office via their online portal: eCO.

There is an excellent guide on Legal Zoom® for copyrighting music that I want to point you to. Check it out here.

Registering your music for copyright does not grant you access to a single penny of your music royalties. In order to get paid, continue reading the rest of this guide.

The Different Types of Music Royalties

Most people don’t realize there are different types of royalties in music and that said royalties are generated in a variety of different ways. First, it is important to know and understand all the different types of music royalties and how they are generated in the first place. Then we will discuss how different types of music royalties are calculated, collected, and (if signing a deal) how to negotiate a fair cut for yourself.

1. What are Streaming Royalties?

Streaming royalties are the fees paid out to the Master Rights owner of the song. In other words, if you “own your masters” there’s a royalty out there for you every time your master recording is streamed on Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, and more.

Think of it as our “copyright owner’s royalty” since the master recording is YOUR intellectual property. So whenever Spotify or Apple Music uses your intellectual property for their profitable business, you deserve to get paid. That means if you are an independent artist that funded and created the studio recording of your song, then you own your own masters and get paid this royalty through your music distributor.

Note that a small portion of your streaming royalties is also paid out via your PRO, even if you are not the owner of the master recording. You learn more about this in the How Are Spotify Royalties Calculated section.

If you are signed to a record deal, and the label pays for your studio time, marketing budget, and touring budget… you most likely don’t own your own masters. In this case, the label gets paid the streaming royalties as the master rights owner, and the artist gets paid a negotiated percentage of the royalty based on the recording contract. You’ll learn more about this later in the How Does The Money Flow section.

2. What are Mechanical Royalties?

Mechanical Royalties are generated through physical or digital reproduction and distribution of your copyrighted songs. This applies to all music formats old and new such as vinyl, CD, cassette, (physical) and digital downloads and streaming through Digital Service Providers (like Spotify and Apple Music). For example, record labels pay a mechanical royalty to a songwriter every time they reproduce and sell a CD of their music.

We call them “mechanicals” because it used to be a mechanical process to reproduce music on vinyl and other physical formats. Now in this digital age, the name stuck and Mechanical Royalties are generated every time your master is REPRODUCED and copied. Even when streaming, a small copy of your song is reproduced on a user’s device every time you use the Spotify app… therefore the master rights holder will earn a Mechanical Royalty for the reproduction of that song file on the device.

Mechanical Royalties are not paid out by your distributor. Instead there are Mechanical Collection Societies (MCS) that pay mechanicals out to the artist directly (if you are independent) or to the record label if you are signed. Turns out that EVERY country has a mechanical collection society that PAYS these royalties.

Thankfully there’s a service called SongTrust. SongTrust Collects Royalties From 98% of The Music Market and acts as your publishing administrator (not a publishing deal) that monitors your work globally, with direct relationships with 65 collection societies and pay sources covering 215 countries and territories. To learn more about publishing administration services and how they work, click here.

By the way, if you want to receive $10 off your SongTrust registration, you should use my affiliate link to activate your discount: Get $10 OFF SongTrust.

To learn more, check out our section on How Mechanical Royalties are Calculated.

Before registering, double check that your Performing Rights Organization (PRO) doesn’t already have a mechanical royalty collection baked into it. In the US, these are totally separate things, so if you’re registered with a US based PRO (BMI, ASCAP) then you will definitely want to register with SongTrust also. However, most notably, PRS for Music in the UK has a mechanical collection society associated with it. The Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society (MCPS) is a branch of PRS for Music. You have to register with them separately (more on this later), but it is to your advantage to register with MCPS if you’re planning to become a PRS member.

3. What are Songwriting Performance Royalties?

The royalties we’ve discussed so far have pertained only to the Master Recording. But there is an entirely separate category of royalties pertaining to the musical composition itself (aka the music and the lyrics). This is where Songwriting Performance Royalties come in.

Performance Royalties are generated through the use of the copyrighted songs themselves (not the recording). Examples of “usage” are when a song is performed, recorded, played or streamed in public. That’s right, even playing a recording of a song is considered a performance.

You’ve experienced this before probably without even realizing it. You know the music over the intercom at Starbucks or at the mall? Yup, those are little performances happening over your head. This isn’t limited to coffee shops or public spaces but also includes any terrestrial radio station (AM/FM), television, clubs, restaurants, bars, live concerts, shopping malls, music streaming services, internet radio, and anywhere else the music plays in public.

You might be wondering how a Songwriting Performance Royalty is different from the royalties previously mentioned above! First, Performance Royalties are collected by your Performing Rights Organization and not by your distributor or mechanical rights society. Secondly, Songwriting Performance Royalties are paid to the Songwriter and Publisher. That means that even if a songwriter is not involved with the recording of a song (think “cover song”) you as the songwriter and/or publisher will still receive your Performance Royalties!

Songwriting Performance Royalties are made up of two parts: 50% Songwriting Share, and 50% Publisher Share.

Let’s use Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face” as a quick example of how Performance Royalties are divided into two halves:

1. Songwriters:

- Lady Gaga (AKA Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta)

- Nadir Khayat is also a songwriter for “Poker Face”

2. Publishers:

- Lady Gaga’s Publishing Company “HOUSE OF GAGA PUBLISHING LLC”

- Nadir Khayat’s Publishing Company “SONGS OF REDONE LLC”

- Sony ATV Publishing also gets a cut of the Publishing Royalties because of the “Publishing Deal” these writers signed.

As you can see, each Songwriter automatically has a publishing counterpart and this is why performance royalties are split 50-50 between Songwriters and Publishers. For more examples, check out How Are Songwriting Performance Royalties Calculated below.

But, there is another type of performance royalty all together…

4. What are Artist Performer & Rightsholder Royalties?

Some countries pay the Performing Artist and the Master Rightsholder a royalty in addition to the Songwriter Performance royalty (mentioned in the prior section). This is not true in the United States which doesn’t have this royalty, so we’ll use the United Kingdom for our example.

In the United Kingdom, PPL pays the Performing Artist (the singer of the song) in addition to the writer of the song who gets paid a traditional Performance Royalty through PRS. Again, in the United States there is not a collection society for this royalty since no royalties are generated.

This isn’t exclusive to the UK and for clarity, PPL collects this type of royalty internationally and distributes to members around the world, not just the UK. So for applicable countries, this royalty is generated in addition to the Mechanical Royalty and the Songwriting Royalty mentioned in the prior sections, which is partly paid out to the Master Rightsholder of the sound recording and the performing artists. In short, there are more royalties available to be collected in the United Kingdom compared to the United States.

Let’s use Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face” as an example again.

Artist Performer & Rightsholder

- Lady Gaga is the featured performer (AKA Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta) so she will earn a Royalty as the Performer.

- Interscope Records is the Master Rightsholder since Lady Gaga is signed to that label.

You might be thinking, can I get my hands on this royalty even if I’m in the United States? The short answer is yes! The US does not have its own phonographic performance society/neighboring rights society, so we suggest registering with the United Kingdom’s PPL.

If you’re based anywhere else (even outside the US or the UK), we also suggest registering with PPL. They have members all over the world, and you won’t have to worry about tax collection at source because PPL was the first music licensing company to be given Qualified Intermediary (QI) status by the US tax authorities – meaning that royalties collected by PPL from the US need not be subject to US withholding tax of 30%.

We’ll talk about registration more in depth in our Where Do I Register to Collect My Music Royalties section.

5. What are Digital Performance Royalties?

Digital Performance Royalties are a relatively new addition to royalty law as digital music streaming became more popular. Digital Performance Royalties, also known as Non-Interactive Streaming royalties are the “digital radio royalty” and are generated whenever your song is played on internet radio platforms like Pandora, SiriusXM, Satellite Radio, Cable TV Channels, and all non-interactive platforms.

Non-interactive means that the listener does not have control over what song gets played next on the “station”—this excludes Pandora Premium, Spotify, and other traditional streaming services where you can pick specific songs to play in your queue. So if you can’t control, or skip to the next tune, then you’re probably generating a Digital Performance Royalty. (Note this does not include non-digital radio, known as “Terrestrial Radio” such as your AM/FM stations.)

Digital Performance Royalties are regional to the United States through the collection society SoundExchange. These guys collect and distribute Digital Performance Royalties for all those non-interactive digital broadcasts I mentioned earlier. In the rest of the world, digital performance royalties are just a part of a larger landscape of neighboring rights that deserve their own section.

So in short, to collect these US-based royalties, check out SoundExchange. And if you’re a non US-based artist you can still register with SoundExchange to benefit from US-based non-interactive digital royalties.

Note that PPL in the UK is affiliated to SoundExchange, so by registering with them you will also be reaping the benefits of this royalty.

So, next time you're enjoying a curated playlist on Pandora or tuning in to SiriusXM, remember: there’s more going on behind the scenes because of non-interactive streaming royalties.

6. What are Neighboring Rights Royalties?

Neighboring Rights Royalties are a broad category of royalties that include song usage generated from other foreign countries as well as rights adjacent to the songwriting rights in the eyes of the law (aka performing royalties rather than songwriting royalties). Each country handles Neighboring Rights Royalties slightly differently. We'll give a general overview below.

Musicians receive these royalties whenever music is “performed” and used in various forms of media, such as music played on the radio, in live performances, or in public spaces. However, in the US, these rights are known by a different name: “digital performance rights” because that is the only type of neighboring right generated in the US by law. Unfortunately the US does not legally recognize neighboring rights in the same way the rest of the world does. The only equivalent are digital performance rights, A.K.A. digital performance royalties/non-interactive royalties (see previous section) i.e. satellite and digital radio (Sirius XM, Pandora).

There also isn’t a national society in the US that will collect neighboring rights even from the parts of the world that do recognize their legal existence. The closest is SoundExchange, but they only collect non-interactive royalties as mentioned above. That’s why we’ll suggest you register with PPL in the UK (more on that later).

Another reason Neighboring Rights are often confused for a geographical type of royalty is, well… Because technically they also are…

Let me explain…

Neighboring Rights (royalties) were established in 1961 at the Rome Convention to set minimum standards for neighboring rights of performers, producers, and broadcasters. However, to actually receive neighboring rights, you must be a citizen of one of the signatory countries.

Canada, The United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Japan, Hungary, Greece, Italy, France, Sweden, Spain, and Poland are just some of the 97 current members.

The United States is not a member. This means if you are a US Citizen, you will not inherently receive neighboring rights royalties at all, unless you register with a foreign society, such as PPL, as mentioned above. This also means that signatories will not receive neighboring rights from usage in the United States.

If you are a citizen of one of the 97 signatory countries of the Rome Convention, you WILL receive neighboring rights royalties through your local neighboring rights society. You can double check this by googling “Your Country of Residence” and “Neighboring Rights Society for Music Recordings” and you should get a featured snippet letting you know which society is applicable. For example, in the UK, your neighboring rights society is PPL.

7. What are Synchronization (Sync) Royalties?

Synchronization Royalties, or Sync Royalties for short, are generated when copyrighted music is paired or ‘synced’ with visual media.

If you’ve ever watched a TV show, commercial, seen a movie in theaters or even on Netflix, you’ll probably notice that there’s a LOT of music being used. As you already know, the usage of music requires a license (permission) and generates a royalty.

Synchronization licenses give the license holder the right to use copyrighted music in films, television, commercials, video games, online streaming, advertisements, and any other type of visual media. Sync licenses are generally sold by Music Publishers and any time the marriage of music and visual media is made, a license is required.

There are no set rates for sync, but there are two main categories:

- Sync License Fees - These are fully negotiable one-time payments to the Master Rights Holder and Songwriter/Publisher with custom rates for each. Factors include the popularity of the song, the production budget, the clout of the artist, and other factors like how much of the song is used and in what context of the film or commercial, etc. The license fee breaks down into two halves:

- The Sync License Fee – This is the fee to legally use the musical composition itself (music and lyrics), which is paid out to the songwriter and publisher (sometimes the same person if the artist is self published).

- Master Recording License Fee – The master recording fee is paid to whoever owns the “master”. This could be the artist, the songwriter, or the label if there is a label involved.

- Songwriting Performance Royalties & Artist Performer Royalties - In addition there are residual royalties from "Performances" - aka any time the work is played on television. There isn’t an exact royalty rate for this either, but depending on the song’s usage in qualifying broadcasts, you may qualify for a "current use" royalty from your PRO. Read this to learn more because it is quite complicated: How BMI handles Television Usage Royalties

Another note, a synchronization license for the musical composition does not automatically include the right to use an existing recording with audiovisual media. That’s right, if you want to use your favorite artist’s version of a song, the licensee will need to purchase BOTH a master use license and the sync license for the composition to cover both copyrighted works. But if your plan is to re-record a brand new version of the song you just licensed, you can get away with only the sync license for the musical composition. Many production companies commission new recordings to save money by purchasing one license and forgoing the Master Use License by producing their own recording.

8. What are Print Music Royalties?

Print Royalties are not as common for recording artists but are a common form of payment for classical and film composers. This type of royalty applies to copyrighted music transcribed to a print piece such as sheet music and then distributed through a print music publisher such as Alfred Music or Hal Leonard. These fees are often paid out to the copyright holder based on the number of copies made of the printed piece.

How to get Paid Royalties as a Musician

Now that we’ve established all the different types of music royalties, it’s logical to wonder how to collect each type of royalty. Our theme in this next section will be determining your musical “role” in the writing and production of a composition or master recording. The more roles you play, the more royalties you qualify for! Let’s dive in.

Master Rights Holder

If you are the master rights holder of the song recording, you qualify for a royalty for certain usages. The master rights holder is usually the individual or company who funded the recording of the song. If you are an independent musician who self-funded and recorded your own original song or cover song, then you are the master rights holder. If you are signed to a record deal and your record label paid for your studio time, then you probably signed away your master rights and the label is the current master rights owner.

Here are the royalties that the master rights holder is entitled to:

- Streaming Royalties

- Mechanical Royalties

- Neighboring Rights Royalties:

- The rightsholder portion of the Artist Performer Royalty (not applicable in the US)

- Digital Performance Royalties/Non-Interactive Royalties

- Master Recording License Fee

Songwriter

Songwriting royalties are perhaps the most widely discussed royalty role. Everyone wants to earn that big fat royalty check from being the “writer” of the song. But what does that mean in real life? Contributing towards the lyrics, melody, production, beat, and sometimes even a creative remix could earn some songwriting credit. Your songwriting percentage is completely negotiable and is usually based on what you bring to the table in the writers room or production session. There are two main schools of thought when approaching songwriting splits: Nashville Style and LA Style.

Nashville style where splits are equal across all writers regardless of contribution, LA style splits are up for more “creative” negotiation.

In LA, music is more diverse and producers are involved in the songwriting process in a much bigger way than ever before in music history. As a result the producer might demand songwriting credit for the contribution of the instrumental. This is why producers often negotiate anywhere from 10-50% of the songwriting credit depending on their “clout.”

In a similar way, having a "feature" on a song will introduce another songwriter who may only write one or two lines for a “hook” and while their lyric contribution may be small, their songwriting cut could be negotiated larger based on the clout being brought to the track.

Here are the royalties that songwriters are entitled to:

- 50% of Performance Royalties (songwriting share)

- Neighboring Rights Royalties

- Up to 50% of the Artist Performer Royalties if the songwriter is also the performer (to be shared by the Contracted Featured Performer, Other Featured Performer and Non-Featured Performer – more on this later)

- Digital Performance Royalties/Non-Interactive Royalties

- Sync Licensing Fees

- Print Music Royalties

Publisher

A music publisher is a company or individual responsible for managing and monetizing the rights to musical compositions. They act as intermediaries between songwriters and the music industry, helping to promote, license, and collect royalties for songs.

If you are an independent artist, you are essentially a “self-published” songwriter and the responsibilities of the publisher fall on your shoulders. Many self-published writers seek out the help of a Publishing Administration Service, more on that in the next section.

In essence, music publishers play a crucial role in “shopping around” a song for opportunities and ensuring that songwriters receive compensation for the usage of their writers’ works. They handle various tasks, including:

- Song Promotion: Publishers work to get songs placed in films, TV shows, commercials, and other media. They also pitch songs to recording artists for potential “cuts” for their next single or album.

- Royalty Collection: Music publishers collect royalties generated from the use of songs in various ways, such as radio airplay, streaming, public performances, and synchronization licenses.

- Licensing: They negotiate licensing agreements with businesses, broadcasters, and streaming platforms to use songs in various contexts.

- Advancing Royalties: Publishers often provide songwriters with advances on future royalties (similar to a record deal) so they can focus solely on songwriting and quit their barista job.

- Administration: They handle the administrative tasks associated with music rights, including tracking usage, calculating royalties, and ensuring timely payments to songwriters.

Music publishers typically earn a percentage of the royalties they collect, and this fee can vary based on the agreement with the songwriter. For self-published songwriters, you’ll want to be intentional about collecting your publishing royalties in addition to your songwriting royalties. To learn more about that, check out our section on Independent Musicians.

Here are the royalties publishers are entitled to:

- Usually 50% of Performance Royalties (publisher’s share)

- A negotiated percentage of any Sync Fees or collected royalties paid to the songwriter according to the Publishing Deal.

Publishing Administrator

A publishing administrator is a service that specializes in helping self-published songwriters or publishing companies manage catalogs, collect royalties, and make payments to their artist roster. A Pub Admin Company handles everything that a traditional publishing company would do in-house, and offers these services to smaller publishers and independent artists who can’t hire and train an in-house staff.

Publishing administrators often charge a percentage of the royalties they collect as their fee. This can be an attractive option for independent songwriters and smaller music publishers who would prefer the smaller 15-25% fee that Pub Admins charge in comparison to signing 50% of their publishing royalties away in a traditional publishing deal. Ultimately, a publishing administrator serves as a valuable partner in managing and maximizing the revenue generated from musical compositions.

Here are the royalties publishing administrators are entitled to:

- 15-25% of the Publisher’s Share of the Performance Royalty.

Music Performer (Artist)

In the United States, performance royalties are only paid out to songwriters and publishers. Thankfully, this is NOT the case in other countries and you can receive royalties as a music performer (aka the person that sings the song). As mentioned before, these royalties can be collected by US-based musicians via PPL, but they are not generated in the US.

The traditional term for a performance rendered by a recording artist on a recording is a “cut”, and you can get paid for cutting songs you have not written, but are the performer.

These royalties are most common in the United Kingdom where the performing artist gets paid in addition to the songwriter.

Music performers will also get paid when performing live at venues and can negotiate a variety of fees:

- Performance Fees

The primary source of income for music performers at concerts is their performance fee, often referred to as a guarantee or simply a "show fee." This fee is negotiated between the artist or their representatives (such as a booking agent) and the concert promoter or venue. It can vary widely depending on the artist's popularity, demand, and the size of the venue.

For established artists, performance fees can be substantial and can make up a significant portion of their income. Lesser-known or emerging artists may receive smaller guarantees, especially when starting their careers.

- Ticket Sales

Ticket sales revenue is another significant component of how music performers get paid for concerts. When you purchase a ticket to a concert, a portion of that money goes toward covering the performer's fee, production costs (like sound and lighting), and the venue's expenses. The remaining revenue, known as the "gate," is typically split between the promoter and the featured artist.

The specific ticket revenue split varies, but it's a critical aspect of a performer's earnings. In some cases, especially for high-profile artists, they may negotiate a percentage of the ticket sales in addition to their performance fee.

- Merchandise Sales

Merchandise sales, including T-shirts, posters, CDs, and other items featuring the artist's branding, are a significant source of income for music performers at concerts. They often set up merchandise booths at the venue, and the revenue generated from merchandise sales goes directly to the artist (if the artist is unsigned).

Fans purchasing merchandise not only get a piece of memorabilia but also directly support the artist they came to see. Merchandise sales can be particularly lucrative, especially for artists with dedicated fan bases.

- Ancillary Revenue Streams

Ancillary is just a fancy word for “extra” and depending on the specific arrangements, music performers may have access to various ancillary revenue streams. These can include a share of concessions sales, VIP experiences, sponsorships, and even a percentage of the parking fees if they're part of the negotiation.

Behind the Scenes Royalties

Now a section for the unsung heroes of the music business. Producers, Managers, Booking Agents, and Session musicians all play a critical part in helping an artist rise to the top. Yet, sometimes it feels like a kick in the gut when the artist gets all the fame and kudos for a song that you poured your heart and soul into producing. But you can still earn your fair share of royalties off the stage in many of these supporting roles.

Producer Royalties

Some producers are paid a flat fee through a Work for Hire Agreement or an advance from a record label for their work. But another way to pay a producer is through a music royalty known as points.

Producer points are also commonly referred to as points, album points, producer percentages, or producer royalties. Producer points are usually negotiated when working with an established record label and are essentially a share of the revenue generated from the commercial exploitation of the music they've worked on.

Points can be negotiated and awarded in a few different ways:

- Negotiation and Fair Compensation:

Negotiations typically occur during the contractual discussions between the producer and the relevant parties, which could include the artist, record label, or music publisher. This stage sets the terms for how the producer will be compensated for their creative contributions.

Producers must advocate for their points during these negotiations to ensure they receive a fair and equitable share of the royalties generated by the music they help create. The outcome of these negotiations can significantly impact the producer's long-term earnings and recognition within the industry.

- Percentage Share of Artist Royalty:

Producer points are commonly calculated as a percentage of the "artist royalty." The artist royalty represents the money generated from various sources directly linked to the music, such as sales, streams, and other income streams. It's essential to note that this is distinct from the total revenue generated, as artists typically receive a percentage of the total revenue.

The percentage share assigned to producer points can vary but often falls within a range of 2% to 5% of the artist's royalty from their record deal. This percentage is a reflection of the value and contribution the producer brings to the project. A higher percentage acknowledges a more significant role in shaping the final music product.

- Album vs. Single Points:

Producers often have the opportunity to negotiate different points for individual songs (singles) and entire albums. This distinction recognizes that not all songs on an album may achieve the same level of commercial success. As such, producers may secure a higher percentage of producer points for singles, which have the potential to become major hits, while album points are generally set at a lower percentage.

This flexibility allows producers to align their compensation with the anticipated success of specific songs, providing an incentive for their involvement in potential chart-toppers.

- Advances and Recoupment:

In some cases, producers may receive an advance against future royalties as part of their compensation package. This advance serves as an upfront payment, providing financial support during the production phase and beyond. However, it's crucial to understand that these advances are not additional earnings but rather prepayments of future royalties.

The concept of recoupment comes into play here. Advances must be recouped, meaning that the producer's share of royalties will first go toward paying back the advance before they start receiving additional payments. Once the advance is fully recouped, any subsequent royalties become earnings for the producer.

Here are some fake scenarios with examples and math calculations to help illustrate how producer points work:

Scenario 1: Single Producer with 3% Points

Scenario: An emerging music producer, Alex, collaborates with an independent artist, Sarah, to produce a single titled "Sunshine Vibes." They agree on a 3% producer point for Alex.

Example:

Total revenue generated from "Sunshine Love" (streams, downloads, and other income sources): $100,000.

Artist royalty via record deal (typically 50% of total revenue): $50,000.

Producer points (3% of artist royalty): 0.03 * $50,000 = $1,500.

In this scenario, Alex would earn $1,500 as producer points for the single "Sunshine Vibes."

Scenario 2: Album with 4% Points for Singles and 2% for Album

Scenario: A renowned producer, Max, collaborates with a popular artist, Chris, on an album titled "Epic Jams." They negotiate a 4% producer point for singles and a 2% point for the entire album.

Example:

Total revenue generated from the album "Lost in Translation" (streams, downloads, and other income sources): $500,000, but 80% of the revenue derived from the two singles on the album totalling $400,000 for singles, and $100,000 for the remaining album tracks

Artist royalty (typically 50% of total revenue): $250,000.

Producer points for singles (4% of artist royalty for singles): 0.04 * $200,000 = $8,000.

Producer points for the album (2% of artist royalty for the album): 0.02 * $100,000 = $2,000.

In this scenario, Max would earn $8,000 for the singles and an additional $2,000 for the album, totaling $10,000 in royalties through producer points.

Session Musician Royalties

Usually, session musicians are paid a flat rate through a Work For Hire Agreement. To receive a free printable work for hire agreement, click here. What this means is the music that session musicians play is as a service only, and once they are paid in full they have no claim to the copyright of the song or any royalties associated with the usage.

However, when it comes to Major Record Labels, there is more to the story because of union agreements. Let’s take a look at this briefly:

Union Agreements: Session musicians who are members of musicians' unions, such as SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) or the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) in the United States or similar organizations in other countries, often receive compensation and royalties through union agreements. These agreements ensure that musicians are fairly compensated for their work on recordings and in other musical projects. Here's how it works:

Scale Payments: Union agreements often specify a minimum "scale" payment that session musicians must receive for their work on a recording. This payment is typically made upfront and is not a royalty but rather a one-time fee for their services.

Residuals or Reuse Fees: In some cases, musicians may receive residuals or reuse fees when the recorded music is used in subsequent ways, such as in films, TV shows, commercials, or compilations. These fees can be considered a form of royalty, ensuring that session musicians continue to earn income when their recordings are reused. Once again, these are paid out through your musicians union.

SoundExchange Royalties: In the United States, SoundExchange collects and distributes digital performance royalties for sound recordings played on non-interactive digital platforms like Pandora and SiriusXM. Session musicians who are credited as featured artists on these recordings can receive a share of these royalties.

It's important to note that not all session musicians are eligible for featured artist royalties. To qualify, they must be credited as featured performers on the recordings and have contracts or agreements in place that specify their entitlement to royalties.

Phonographic Performance Royalties: in other parts of the world, particularly in the UK, session musicians can be entitled to 5% share of the Artist Performer Royalty, even if they are only credited as a non-featured performer. In fact, to qualify for this share, you must be credited specifically as a “non-featured performer” on PPL. We’ll discuss the different levels of “feature” available to a performer within PPL later.

If you are a non-union session musician, you’ll want to structure your services using a Work For Hire agreement so you get paid in full upon rendering your services. Here is a free Work For Hire PDF contract that you can download and use.

Work For Hire Agreement (Free Download)

Record Label Royalties

We are going to go much more in-depth into Record Label Royalties and the percentages in the next section How Does the Money Flow. As a quick reference, record labels can keep a cut anywhere from 50-90% of your earnings. It is an industry norm for a new artist to only receive 10-16% of their sales. The reason for this incredibly high (or low depending on your point of view) percentage is that record labels take on all the financial risk that artists could never imagine burdening on their own.

Here are some common scenarios for record label percentages:

50/50 Split: In some cases, particularly for independent artists or artists with significant bargaining power, a 50/50 split may be negotiated. This means that the artist and the label each receive 50% of the net profits from music sales, streams, and other income sources related to the recording.

Standard Percentage Deals: Many artists, especially those signed to a major record deal, are subject to standard percentage deals where the label typically takes a more substantial share. In such cases, the label may take 70% or more of the net profits, leaving the artist with a smaller percentage.

Advance Repayment: In addition to the percentage split, some record deals involve an upfront advance payment to the artist. This advance must be recouped (earned back) by the label before the artist starts receiving additional earnings from the recording. The recoupment terms can vary and may impact the overall percentage taken by the label.

Tiered Deals: Some record label contracts may have tiered structures, where the label's percentage changes based on certain milestones, such as album sales or streaming numbers. For example, the label might take a higher percentage initially but offer a more favorable split once specific sales targets are reached.

Ancillary Income: Record labels may also negotiate a share of ancillary income sources, such as merchandise sales, touring revenue, and licensing deals. These arrangements can vary and are typically negotiated separately from recording deals.

360 Deals: In some cases, record labels may enter into "360 deals," where they participate in a broader range of an artist's income streams beyond just recorded music sales. This could include a percentage of revenue from live performances, merchandise, endorsements, and more.

For more information, read our dedicated post What is a 360 Deal

Marketing and breaking a new artist costs a lot of money and it's no secret that most artists that labels sign don't even turn a profit, meaning that Labels need to rely on their successful acts to pay the debts of the failed acts. To learn more about how the money flows, check out the next section.

Artist Manager Cuts

An Artist Manager is one of the most important people in your life. They guide your business decisions such as deciding whether or not to do a record deal. They also are a part of the creative process such as selecting a producer. They are also your number one fan and biggest cheerleader (other than mom of course.) It is because of their huge importance to an artists' career that they warrant a 15-20% cut of your earnings as a new artist. These percentages are applied to your gross earnings, meaning that this is a percentage off the top of what you make (not what you keep). Managers also receive 15-20% of music royalties you earn from past songs and opportunities, even if they weren't your manager at the time. This might seem a little strange, but your manager is supposed to propel your career to the next level. If that's not happening, try to find another manager.

Booking Agent Cuts

Artist Managers and Booking Agents often get grouped together, but they couldn't be more different. Unlike Artist Managers who are involved in every aspect of your music career, Booking Agents primarily deal with booking live concerts and other personal appearances. Another large distinction between Artist Managers and Booking Agents is that while anyone can become a manager (for better or for worse) a career as a Booking Agent is a highly regulated field. Booking Agents are regulated by the unions: AFM (American Federation of Musicians) for musicians, SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) for vocalists and actors on recorded media, and Actors' Equity Association for live stage. These unions put a cap on how much the agents can charge, roughly 10%. The contracts are also provided by the unions so read them carefully to make sure you're not signing anything that you will regret.

How Are Artist Royalties Calculated?

When talking about music royalties for performing artists, there are the royalties that are paid from your record label, and then the royalties owed to you through the collection societies mentioned in the prior sections. If you are an independent artist, you’ll receive 100% of income from gross sales, concerts, sponsorships, etc. As a signed artist, your record label takes a cut of that ancillary income. There is a range of acceptable amounts based on your clout as an artist. By clout, I mean how many fans you have, and your command over earning an income from those fans. If you are a new artist your clout will be low, but if you have a lot of buzz this can quickly increase your clout level to compare with other mid-level Artists. And then finally we have the superstars who are already commanding millions of streams and making lots of money for their managers and labels.

Let’s take a look at the royalty amounts generated by your music usage, and then how much a label would take if you were a signed artist.

How Are Spotify Royalties Calculated?

If you want to learn more about Spotify and how it works, check out this guide here.

If you want to calculate how much you’ll earn from your streams, use my custom Spotify Royalty Calculator.

Spotify Royalty Calculator

Remember, the Mechanical portion of your Streaming Royalties are NOT collected by your Distributor or Performing Rights Organization. They are collected by another party called a Mechanical Licensing Agent/Mechanical Collection Society. The most popular being the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC) and SongTrust. To learn more about how to collect from MLAs and MCSs, keep reading on.

There is also a small portion of your streaming royalties that are collected by your PRO. In the United States, streaming performance royalties are calculated based on the company's gross revenue (this is covered in more detail below). In Europe the powers that be have decided to consider a stream roughly 75% public performance and 25% mechanical reproduction and a download is the exact opposite.

While the bulk of the public performance portion of your streaming royalties is collected by your distributor, a tiny fraction gets collected by your PRO as “online use” of your song. Sounds confusing? That’s because it is. Even the PROs themselves are confused (trust me, we’ve been on the phone to them). Across the board the answer we got from the PROs was that streaming royalties are so new the industry is still adapting and playing catch up.

For now, just know that 75% of your Spotify and other streaming royalties will get collected by your distributor and that you can also expect a fraction of those 75% to be paid via your PRO each year. In Europe, this is in addition to the remaining 25% of that royalty that will be collected for its mechanical use via your MLA (e.g. SongTrust) or MCS (e.g. MCPS in the UK).

Just a quick note that this 75-25 split for a streaming royalty is only true in Europe and for Spotify. When speaking to PROs we got confirmation that they themselves are not given detailed breakdowns of how these royalties get split by other streaming services (such as Apple Music, Deezer, Tidal etc.). Furthermore, the 75-25 (performance vs. mechanical) royalty split is not global, each territory makes their own rules.

How Are Mechanical Royalties Calculated?

In the United States, the Songwriter and the Publisher get paid Mechanical Royalties every time a song is reproduced. Remember, a reproduction includes physical sales, digital downloads, and streams.

The rate of mechanical royalties is set by the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), and it is based on the type of format and the price of the song. For example, the rate for a CD is currently $0.0911 per song, while the rate for a digital download is currently $0.0175 per song.

Mechanical royalty rates differ based on the format and for streaming, the royalty is a percentage and not a fixed amount. The mechanical royalty for a stream (on Spotify for example) is a percentage of a company's revenue earned by the streaming service divided by the usage and qualifying artists.

The formula for calculating Mechanical Royalties is as follows:

Mechanical Royalty = max(Spotify Revenue * CRB Revenue Rate, Label Costs * CRB Label Rate) - (Spotify Revenue * PRO Rate)

And for ensuring the minimum mechanical royalty per stream:

Final Mechanical Royalty = max(Mechanical Royalty, Total Streams * Minimum Mechanical Royalty per Stream)

This is not a simple calculation, but we’ll explain it in small bits so we can tackle this complex royalty together:

- Calculate the "All In" Royalty Based on Spotify's Revenue

This step involves determining the total royalty pool available for songwriters and publishers based on Spotify’s overall revenue. The Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) sets a rate which is a fixed percentage of Spotify's gross revenue. This percentage is applied to the monthly gross revenue that Spotify reports to determine how much money will be allocated as royalties for the compositions. For example, if the CRB sets the rate at 13.3% and Spotify's revenue for January is $100 million, then $13.3 million is allocated for "All In" royalty for that month.

- Calculate an Alternate "All In" Royalty Based on Label Costs

In this step, the CRB also sets a percentage that is applied to the total amount of royalties allocated for sound recordings, which is referred to as "Label Costs." These costs represent the combined total of what record labels earn from Spotify in terms of sound recording royalties. The purpose of this calculation is to ensure that the royalties for the compositions are balanced in relation to what is paid out for the recordings. This means that if labels earn a significant amount from streams, there’s also a significant portion set aside for songwriters and publishers.

- Compare the Two Calculations and Select the Higher Amount

After determining the royalty pools from Spotify’s gross revenue and label costs, both amounts are compared, and the higher value is chosen as the "All In" royalty for compositions and songs for that month. This ensures that songwriters and publishers benefit from the most favorable economic conditions each month, whether it be a good month for Spotify's overall revenue or a month where label costs are particularly high due to streaming.

- Determine the Public Performance Royalty

This involves calculating the amount due for the right of public performance of the compositions. Performing Rights Organizations (PROs) such as ASCAP and BMI negotiate rates with Spotify, which are a percentage of Spotify's monthly gross revenue. This percentage is dedicated to paying for the public performance rights of compositions streamed on the platform. The actual rate is influenced by agreements and, in the case of disputes, can be set by rate court proceedings.

- Subtract the Public Performance Royalty from the "All In" Royalty

Once the public performance royalty has been established, it is subtracted from the "All In" royalty amount determined earlier. The remaining balance is then allocated as the mechanical royalty, which compensates the right of reproduction (the creation of copies of the composition, physical or digital). This ensures that there is a separate recognition and compensation for the composition’s reproduction in addition to its public performance.

- Ensure a Minimum Mechanical Royalty Per Stream

The final consideration is the implementation of a floor on mechanical royalties per stream. This ensures that, irrespective of the public performance royalties, there is a guaranteed minimum amount that songwriters and publishers will earn per stream for the reproduction rights. This is critical because it protects the mechanical royalty from being too diluted, especially if the public performance royalties represent a large portion of Spotify's revenue, which would leave little for mechanical royalties.

Royalty Increases

At the time of writing, the Copyright Royalty Board has set the streaming mechanical royalty rate to 15.1% of gross streaming revenue and further royalty increases have already been announced from 2023-2027:

- In 2023 (starting January 1), songwriters and music publishers will be paid a headline rate of 15.1% of a US service’s revenue;

- in 2024, this will increase to 15.2%;

- in 2025, it will increase to 15.25%;

- in 2026 it will increase to 15.3%;

- and in 2027 it will reach 15.35%.

Because mechanicals are split between the Songwriter and the Publisher, self-published independent artists will receive 100% of their mechanical royalties since they occupy both roles in the industry. Songwriters signed to a publishing deal will earn the songwriter's share of mechanical royalties (50%), and the publisher's share (50%) will be sent to the publisher. Mechanical royalties are collected and paid out by your publisher, publishing administrator or publishing service such as Songtrust or CD Baby Stages. Your distributor will not send you any mechanical royalties so if you are an independent artist be sure to register with a publishing service like SongTrust to collect your mechanical royalties.

Note: Your total Spotify Royalty is your Master Use Royalty + Performance Royalty + Mechanical Royalty combined.

Sometimes, you just wanna know what a stream is worth. All these individual royalties are just a piece of one (very small) total streaming royalty. Spotify used to give an estimation of their royalty rate on their FAQ page, but have since taken that page down. Fortunately for you guys, I have it saved in this guide for you. But who knows if these numbers are still accurate—Spotify surely isn't saying anything:

"Recently, [the above] variables have led to an average “per stream” payout to rights holders of between $0.006 and $0.0084. This combines activity across our tiers of service. The effective average “per stream” payout generated by our Premium subscribers is considerably higher."

Take this with a grain of salt, I know I will. Here is a cool Spotify royalty calculator you can bookmark if you are having a hard time remembering these decimals. This calculator assumes the Spotify royalty rate is $0.0038 per stream which might be closer to reality. Also, here’s a link to some tissues so you can wipe your tears after discovering how little you will be making from Spotify streams.

Wholesale Royalties from Physical Sales

Physical CDs might be on their way out, but if you are signed to a major or independent record label, they will probably still be an ingredient in your royalty income for years to come. And even if CDs go the way of the dinosaur, you can ironically apply this same concept to vinyl sales.

When a CD is sold, the artist is typically paid a royalty based on the wholesale price of the CD, not the retail price. This is because the record label sells the CDs to retailers at a wholesale price, which is lower than the retail price that consumers pay. The wholesale price is the basis for calculating the artist's royalty.

Here's a simplified breakdown of how these royalties are typically calculated:

Wholesale Price: This is the price that retailers pay to the label for each CD. It is less than the retail price.

Artist Royalty Rate: This is the percentage of the wholesale price that is paid to the artist. This rate is negotiated when the artist signs the record contract. It can vary significantly depending on the artist's leverage and the label's standard practices, but a common range might be anywhere from 10% to 20%.

Royalty Calculation: The artist's royalty is calculated by multiplying the wholesale price of the CD by the artist's royalty rate.

For example, if the wholesale price of a CD is $10 and the artist's royalty rate is 15%, the royalty per CD sold would be:

$10 × 0.15 = $1.50 per CD.

Then add the total number of sales to find your total revenue from all CD/ Vinyl sales. Here is the basic concept:

Number of Sales

Wholesale Price

Royalty Rate

X ________________________

Total Royalties Earned

A real-world example: if you are selling an album at a wholesale price of $10 and your royalty rate is 15%, you earn $1.50 per album sale. The remaining $8.50 would go to your record label (assuming you’ve paid off your advance).

Let’s take a look at these deductions a bit closer, starting with recouping your artist advance as a signed artist:

Recoupment: Often, royalties are not paid until the label has recouped certain expenses, such as recording costs, advances paid to the artist, marketing and promotional expenses, etc. This is known as recoupment. Only after these costs have been recouped will the artist start receiving royalty payments.

Deductions: There might be other deductions taken out before the artist receives their royalty. These could include packaging charges, breakage fees (historically accounted for even though CDs are less prone to breakage than vinyl), and in some cases, a portion of promotional costs.

Returns: Retailers have the right to return unsold CDs for a refund. These returns can affect the royalties paid; if a CD is returned, the royalty attributed to that sale may be debited from the artist's account.

Royalty Flow Examples

Now, remember when I talked about artist clout? That is how your royalty rate is determined. If you are a new artist, you might fall anywhere from the 13-16% range. For a mid-level artist who has sold over 100,000 albums (not streams, we are talking about cold hard sales), you can command 15-18%. The superstar artists that are at the top of the industry can command upwards of 18-20%. Never will you see a 50% cut from a major record deal, but if you sign to an Indie Record Label, your cut could be as high as 50%. Check out the graphic below:

If you are NOT signed to a record label, you can ignore the above and instead trust that your Digital Distribution Service (CD Baby, Landr, Distrokid, TuneCore, etc.) is paying out roughly 86-100% of what is owed to you, depending on which service you use.

This section covered mechanical royalties only, so to get the rest of the picture, jump down to Performance Royalties and to How Does The Money Flow to learn more.

How Are Songwriting Performance Royalties Calculated

Performance Royalties are generated when copyrighted works are performed, recorded, played or streamed in public. This includes radio stations, television, bars, restaurants, clubs, live concerts, music streaming services, and anywhere else the music plays in public. As I mentioned earlier in the guide, Performance Royalties exist in two parts: Songwriter Royalties, and Publishing Royalties. Both are collected and paid out by your Performing Rights Organization (PRO).

Performing Rights Organizations (PRO)

Performing Rights Organizations collect Performance Royalties for artists that affiliate with their organization. In the United States, there are three major Performing Rights Organizations: BMI (Broadcast Music, Incorporated), ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), and SESAC (now it only stands for “SESAC”). BMI, ASCAP, and SESAC all pretty much do the same thing except that SESAC is drastically smaller than its other counterparts and only has about 10% of America’s performing artists. SESAC is also the only exclusively invite-only performing rights organization. BMI and ASCAP anyone can join and are non-profit organizations so you will most likely choose one of these two when you start out (especially with SESAC being invite-only).

If you are not affiliated with a Performing Rights Organization, you are missing out on two valuable music royalties: Songwriter Royalties, and Publishing Royalties. Once you are affiliated with a PRO, register your songs to begin receiving your songwriter and publishing royalties. Here is a guide on exactly how to do that: How to Register on BMI.

The calculation of performance royalties is complex and varies by PRO. However, they typically involve several factors, including:

License Fees: PROs collect license fees from music users such as radio stations, TV networks, bars, live venues, and streaming services. The size and reach of the licensee (e.g., a small local radio station vs. a national TV network) impact the fee amount.

Performance Usage: The royalties are then distributed based on the frequency and context in which the songs are played. For example, music played on a prime-time TV show will earn more than music played on a late-night local broadcast.

Cue Sheets and Playlists: For television and film, cue sheets are submitted detailing all the music used. Radio stations and live venues submit playlists. Digital services like Spotify use digital logs.

Weighting: The PROs apply a weighting system to different types of performances. For instance, they consider factors such as the time of day a song is played (prime time vs. off-peak), the size of the audience, and the type of establishment or service broadcasting the music.

Distribution Formulas: Each PRO has its own complex formula to calculate payments, which includes the weighting mentioned above, as well as other factors like the type of performance (feature performance, theme, background, etc.), and the songwriter's or publisher's share as per their agreement with the PRO.

Surveying and Sampling: Because tracking every single performance is impractical, PROs often use a system of surveys and sampling to estimate usage for venues and services that are not monitored on a play-by-play basis.

Members' Agreements: The distribution of royalties is also affected by the individual agreements that songwriters and publishers have with the PROs, which outline the share of royalties distributed between them.

Here is a simplified formula based on everything above:

Royalty Payment = (License Fees * Usage Weight) / Total Assessed Performances

Keep in mind that this formula is an oversimplified representation of the process that Performance Rights Organizations (PROs) use to calculate royalties. Each PRO has its own detailed and proprietary methodology that incorporates various factors and data points to determine the actual royalty payments.

Now let’s dive into the two parts of a Performance Royalty that is paid out 50/50 to Songwriters and Publishers.

1. Songwriter Royalties

When registering a song with your PRO, you will notice that your Performance Royalty is actually split 50/50 into two sub-royalties: Songwriting and Publishing. Songwriter Royalties will always be paid out to the credited songwriters of the composition. There is absolutely nothing a record label, publisher, producer, manager, or bandmate can do to take this royalty away from you. If you are credited properly, you will get paid (given you have a qualifying amount of “usage” as explained above).

2. Publishing Royalties

Publishing makes up the other 50% of the Performance Royalty and, unlike Songwriter Royalties, Publishing can be assigned to outside entities called publishing companies. Music Publishing Companies temporarily take ownership of your songs and manage the lifespan and monetary potential for your music. But if you are not signed to a publishing deal with a Publishing Company, you’ll need to collect your publishing royalties as a “self-published” musician, otherwise you might be missing out on 50% of your Performance Royalties! To avoid this, you can enlist the services of a Publishing Administration Company who will collect your Publishing Royalties on your behalf. To learn more about this, check out our section on Independent Musicians.

How are Artist Performer Royalties Calculated?

Artist performance royalty income is split 50-50 between the master recording rights holder and all the performers listed on that recording’s line up.

The varying amount of each performer's percentage of revenue depends on their contribution category.

With PPL in the UK for example, there are 3 categories a performer can fall into: 1. Contracted Featured Performer (CFP), 2. Other Featured Performer (OFP), 3. Non-Featured Performer (NFP).

These get listed in the line up when a song is submitted to PPL, which defines everyone's royalty income.

The CFP is allocated approximately 60% of the recording’s performer royalties, the OFP gets 30% and the NFP gets approximately the remaining 10%.

These values are just rough guides of how much of the recording’s performer royalty pool each performer can expect to receive.

Carrying on with Lady Gaga’s "Telephone" as our case study:

- Lady Gaga is Contracted Featured Performer

- Beyonce is Other Featured Performer

- Any other performers: Non-Featured Performer

If you’ve used a work for hire agreement for all the performers on your track, then you can claim 90% of this royalty as the featured artist who composed the music and award 10% of this royalty to your non-featured performers who were hired to perform it in the studio.

In this case, think “John Williams”, he’s the featured artist and composer of his film music tracks, but he doesn’t perform every instrument, the film studio hires an orchestra to do so for him.

How are Digital Performance Royalties Calculated?

Digital Performance Royalties are regional to the United States through the collection society SoundExchange. These guys collect and distribute Digital Performance Royalties for all those non-interactive digital broadcasts I mentioned earlier. In the rest of the world, digital performance royalties are just a part of a larger landscape of neighboring rights and deserves its own section.

But for US-based musicians, here’s what you need to know about Digital Performance Royalties and SoundExchange:

The digital performance royalty rates paid are set by the U.S. Copyright Royalties Board.

- 50% goes to the Master Rights Holder of the Sound Recording

- 45% to the Featured Artist (aka the Recording Artist)

- 5% goes to session musicians and backup singers (you need to be an active unionized SagAftra member to claim this remaining 5%)

How does this affect me in the real world? US-based recording artists who record material written by other writers can really benefit from Digital Performance Royalties since the royalty is paid out to Master Rights Holders and Featured Artists.

If you’re a non US-based artist you can still register with SoundExchange to benefit from US-based digital royalties.

Both US and Non-US musicians have the option to register with PPL in the UK. They have a partnership with SoundExchange and will collect all digital performance royalties on your behalf.

How Does the Money Flow?

Earlier we covered how money flows from Record Labels and Digital Distributors in the Mechanical Royalties section. But there is more money out there for you to collect and this could be the difference between being able to pay rent or not! The bad part is that this is where it starts to get complicated when it comes to on-demand streaming platforms such as Spotify, Rdio, Beats, or Rhapsody. Depending on your status as an artist (meaning whether you are signed to a Major Record Label, Independent Label, or are an Indie Artist yourself) the flow of money changes drastically. Let's take a look at how the money flows.

1. Major Record Labels

Let's start above the dashed line in the red where we deal with the Songwriting Copyright. The streaming music royalty for the music composition is split between PROs as a Performance Royalty and publishers as a Mechanical Royalty after the publisher takes their cut for collecting the money in the first place. PROs then subsequently pay the appropriate splits to the songwriter and publisher of the song.

Below the horizontal dashed line on the graphic, we have the flow of money for the Sound Recording Copyright. This is paid directly to the record label and then depending on the details of your record contract, you will receive 10-50% just as we discussed above in the Record Label Royalties section.

2. Indie Record Labels

For independent labels, Mechanical Royalties pass through a mechanical licensing or publishing administrator. Publishing Administration takes 15-20% depending on the service agreement and then the Publisher, just like before, takes another 50% on top of that before hitting the songwriter's bank account. The flow of money for the Sound Recording also has an extra player. Aggregators are a conduit to help distribute your music globally through digital stores and streaming platforms, basically like CD Baby but on steroids. Aggregators take a percentage of every sale before the funds reach the record label's bank account. Lastly, the artist gets paid their cut—which is usually much higher when compared to Major Record Labels.

3. Independent Musicians

Lastly we have independent musicians. Although it’s fun and important to learn about the music business at large, this section here is most likely what will apply to you the most. I’ll go a little extra in-depth so that you can feel completely confident in how your money comes in.

For Songwriter Royalties, independent artists act very similarly to independent record labels. The major difference is that you will need to seek out your own mechanical licensing agent or publishing administrator—this is no small task. Landing a pub admin deal is based on your clout as an artist, as well as your ability to earn dolla dolla bills. An excellent alternative for many artists is a publishing administration service such as CD Baby Stages, Songtrust, or TuneCore. For a small fee, publishing administration services collect publishing on your behalf while retaining an additional percentage of everything they collect. This is an excellent option for independent musicians who need to outsource their publishing.

For Sound Recordings, indie musicians are again very similar to independent record labels. The difference is that aggregators (aka distributors) for independent musicians are limited to digital distribution. For a small fee, a digital distributor such as CD Baby, Distrokid, or TuneCore will digitally release your music across a variety of streaming sites and music retailers. Same as before, digital distributors might take a percentage of every sale before the funds reach your bank account, or charge you a membership fee to keep 100% of your royalties, or some other pricing model. Either way, distributors usually take 15% or less. If you were signed, your record label would take a hefty cut of your earnings at this point anyways, but the benefit of being independent is that you get to choose how much to keep through the selection of your distributor. If you want a distributor that lets you keep 100% of your royalties, you should check out LANDR.

Want to learn more about the music industry and how to collect royalties? Keep reading!

Where Do I Register to Collect My Music Royalties? (In 4 steps)

Overview:

With simplicity in mind, here is the Indie Music Academy’s official recommendation for indie musicians to be able to collect all the different types of royalties available to them at a glance. You won't need a major record deal, you'll just need to set up this musical eco-system and then create a strong marketing strategy. If you want help creating your marketing game plan, read on.

You’ll only need to register in 4 places:

-

- Distributor (Landr (our favorite), CD Baby, TuneCore, Landr etc. – covers your streaming royalties)

- SongTrust (covers your mechanical royalties worldwide, though PRS members in the UK should favor registering with MCPS, and in that case there is no need to register twice)

- Local PRO (BMI, ASCAP, SESAC in the US, PRS in the UK etc. – covers your songwriting performance royalties)

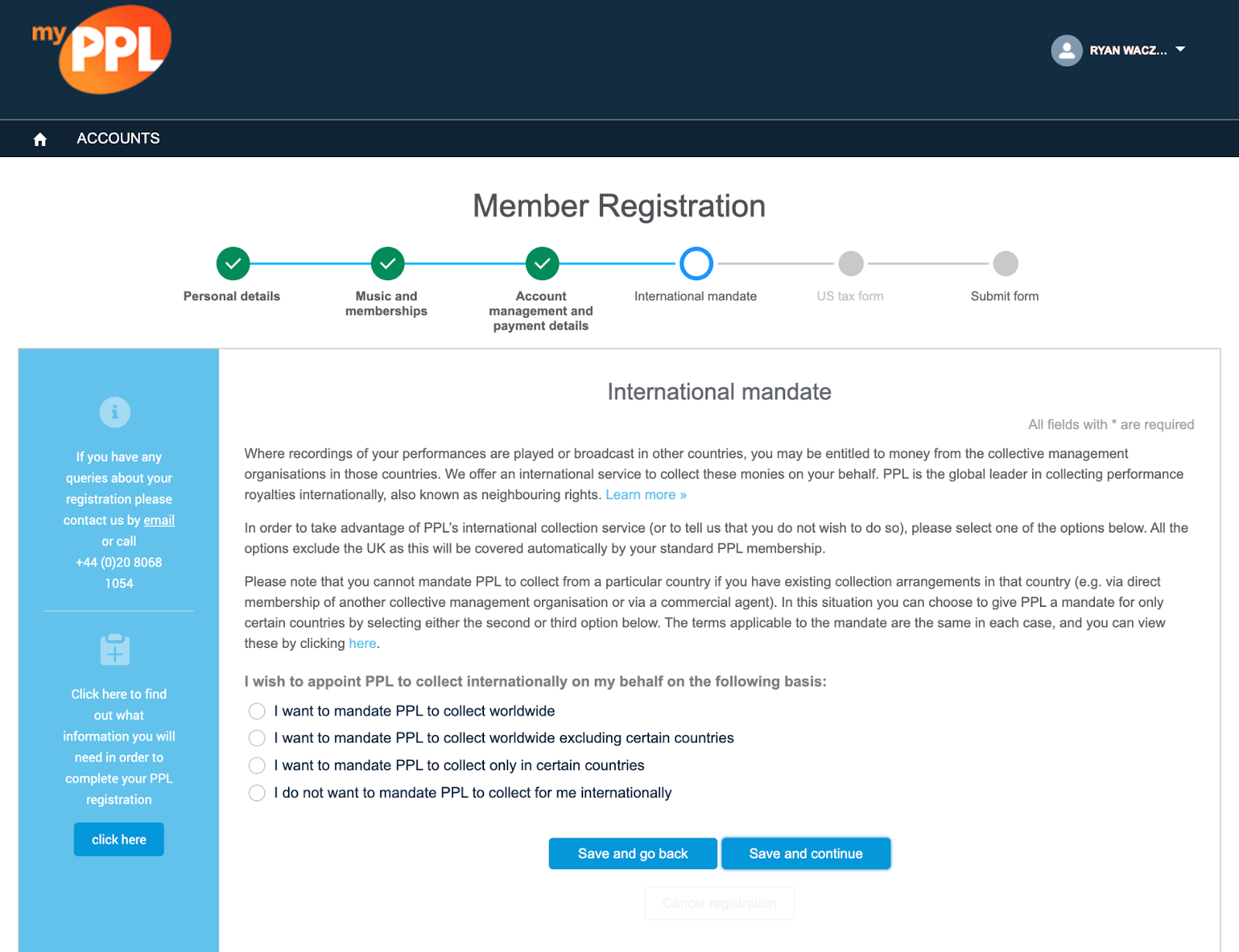

- Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) - Based in the UK but available for international members including US-Based artists – this covers artist performer royalties, digital performance royalties/non-interactive royalties (interfaces with SoundExchange), and neighboring rights from all applicable territories (signatories of the Rome Convention). Note that US based artists will not receive all types of neighboring rights royalties because the US is not part of the Rome Convention. However, by signing up to PPL you can qualify for certain exceptions as a US-based artist. For example, if you were to record your music outside of the USA i.e. in the Netherlands, this would allow you to receive more forms of neighboring rights as the country of performance falls under a Rome Convention territory.

1. Music Distributor